Killer Whale Movements

Classification

Killer Whale, largest member of the dolphin family belongs to the

family Delphinidae of the suborder Odontoceti, order Cetacea. It is classified

as Orcinus Orca.

Distribution

Killer whales occur in more parts of the world than probably any

other cetacean. They occur in all oceans, both in the open ocean and close

to shore, but are more common in the colder, more productive waters of

both hemispheres than in the Tropics. Resident populations may cover an

area of several hundred square kilometers. Transient populations often

move through an area rapidly, swimming more than 1000 km along a shoreline

in a matter of days.

Appearance

Killer whales are black or deep brown overall, with striking white

patches above the eye and from the lower jaw to the belly, and a fainter

grayish-white saddle patch just under and behind the dorsal fin. Males

are somewhat larger than females, with mature females reaching lengths

of up to 8.5 m, and mature males reaching lengths of up to 9.8 m. All killer

whales have a prominent triangular dorsal fin in the middle of the back,

but that of the adult male may grow to 1.8 m tall. The flippers of both

sexes are large and oval, unlike those of any other toothed whale.

Diet

Killer whales may be solitary or live in-groups of 2 to more than

50 animals. They feed on fish, squid, marine birds, pinnipeds, and even

other cetaceans. They generally cooperate during hunting, especially when

feeding on large, warm-blooded animals such as penguins, seals, and porpoises.

Killer whales have even been known to prey on blue whales, the largest

species on earth. In most areas, killer whales have specialized feeding

habits. In the Pacific Northwest of the United States and the Pacific Provinces

of Canada, for example, resident populations feed mainly on salmon and

other near-shore fishes, while transient populations feed primarily on

harbor seals and porpoises. In several places in the Southern Hemisphere

they habitually beach themselves as they rush ashore to take seals or sea

lions in the turbulent surf zone, moving back to deeper water afterward.

Killer whales use echolocation to gather information about their surroundings—that

is, they send out high-frequency clicks that bounce off prey and other

objects and they interpret the returning echoes. Killer whales communicate

by means of rapid-fire click trains that sound like rasps and screams,

although when they are on the prowl for marine mammals, which have acute

underwater hearing, they can be silent for hours at a time.

Breeding

Groups of killer whales seem to be remarkably stable, with males

and females staying in their natal pods, or groups, for life. Consequently,

researchers believe that, to keep inbreeding to a minimum, mating does

not occur between members of the same pod as often as it does between members

of different pods. The female gives birth to a single calf 16 or 17 months

after mating. The calf is nursed for 14 to 18 months.

Human Impact

Killer whales are an important subject of mythology for many indigenous

peoples, especially the Native Americans of the Pacific Northwest. The

whales have not been hunted extensively by humans, although they have been

hunted by some shore whaling operations, and some individuals have been

taken as aquarium show animals from the waters around the Pacific Northwest

and Iceland. Killer whales are perceived by many near-shore fishermen to

be in competition with human fishing activity.

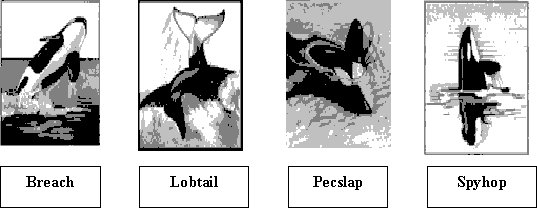

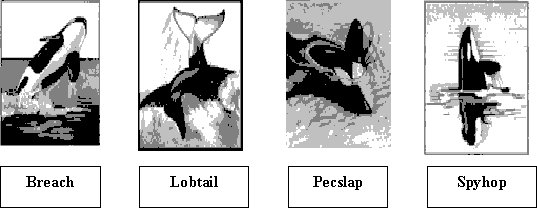

Killer Whale Movements